___________________

MJN: Having grown up in the family of classical musicians, I

have deep appreciation for historical novels featuring the lives of composers

and musicians - and often the lesser known figures who were unfairly obscured. How

do you balance the ration of iconic and obscure characters?

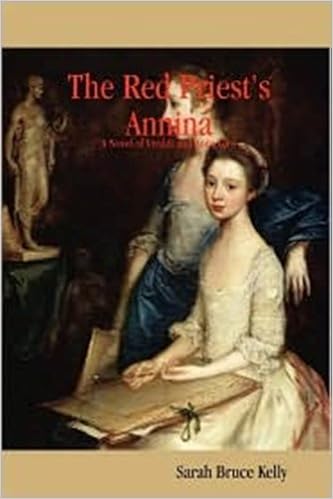

SBK: Historical novels about composers and

musicians are rare. I realized this when I conceived the idea for my first

novel, The Red Priest’s Annina, and consequently I had no real “model”

to help guide me. I think the reason for this dearth of music-related

historical fiction is the necessity for an author to not only be intimately

familiar with musical terminology and techniques, but ideally to have

experience themselves in the performing arts. Fortunately my long background in

musical performance and education, along with my MA in music history and

research, gave me the necessary tools to portray historical musicians

convincingly within the context of the time and culture in which they lived.

Balancing

well-known characters, Vivaldi for instance, with more obscure characters, such

his protégée, Annina Girò, is an intriguing challenge but a challenge

nonetheless. Painstaking and meticulous research is the key, with a bit of

informed imagination thrown in. Historical letters, diaries, memoirs, reviews,

and other documents are helpful, but even more so are the “hunches” that come

about unexpectedly from less concrete sources. For example, I spent years

studying the music Vivaldi wrote for Girò, and the more I got to know her music

the better I got to know her as a person. Not only that, but the touching

nuances of the music he was inspired to create for her say a great deal about

the nature of their artistic and personal relationship. When such hunches are

backed up by documentary evidence something indeed “clicks,” and the story and

characters become all the more real.

MJN: The Red Priest's Annina is said to be written for

preteen and teen girls. I am happy to see so many historical novels targeted at

the young female readership. I have a friend who's an English teacher, and she

said that it's very hard to convince teenage girls to read historical fiction.

The common complaint they hear is, "What does this have to do with real

life?"

SBK: Many historical novels for young readers

focus on some sort of physical action or adventure set in a particular time and

place and often fall short of creating characters that young people can relate

to on an emotional level. These “costume dramas,”as they are sometimes called,

stem from models put forth by the entertainment industry, and their lack of

psychological depth usually fails to sustain the interest of young readers.

When I

first conceived the idea for The Red Priest’s Annina I had envisioned

Annina’s story as engaging young girls in particular. When the finished product

started to attract attention I was pleasantly surprised to learn that not only

girls, but boys as well as men and women of all ages were equally taken with

the story. I believe this was due to the deeply emotional nature of Annina’s

music which, as I mentioned above, made her so real for me that I was able to

portray her feelings, fears and desires in ways that made her real for readers.

This is what all readers, including young people, love to experience in

stories. If they can identify with a character on an emotional level they can

relate that character’s story to their own lives.

MJN: This is the second book that features a contralto. Last

year I read a novel "Goddess" about a French contralto Julie

d'Aubigny. My father was an operatic coach, and he told me that contraltos were

not in demand, and it was hard for a vocalist with that range to reach the same

diva status seemingly reserved for sopranos. There simply aren't enough leading

roles written for contraltos.

SBK: It’s true that there are few starring roles

in opera for contraltos. However Annina Girò was a mezzo soprano, a voice type

that was quite popular in the 18thcentury. This is why current-day

mezzos such as Cecelia Bartoli and Anne Sofie von Otter focus largely on the

Baroque era for their performance repertoire.

Keep

in mind also that the real super stars of 18th-century opera were

the castrati, castrated males. The term “diva” (goddess) didn’t come about

until the late 19thcentury, in connection with the “grand operas” of

Verdi and others whose works now dominate the stages of most opera houses. Vivaldi

himself favored the warmer, richer tones of the mezzo voice and wrote many

dazzling prima donna roles for Girò in that vocal range. Orlando Furioso,La

Griselda, and Rosmira Fidele are just a few examples.

MJN: In the past

decades, the Catholic Church has been subject of scrutiny. Liberal media loves

to demonize Catholic priests as predatory and hypocritical. So when you see a religious

figure portrayed in a benevolent, liberating light, it's refreshing.

SBK: An

intensive study of Vivaldi’s life and work is indeed gratifying and refreshing,

not to mention fascinating. He was a Catholic priest who devoted his life to

creating some of the most sparkling and innovative music of the 18th century.

His many hundreds of concertos, operas, and sacred works were composed in

praise of God and Mary, expressed by the unique monogram he inscribed at the

top of his musical scores, which means: “Praise be to God, and to Mary, the

Blessed Mother of God, Amen.

He was

blessed with extraordinary talents, which he used to put his faith into action.

Not only was he a brilliant composer and musician, he was also a gifted teacher

who shared the gift of music with countless students. Due to a respiratory

ailment he had since birth, he was unable to say Mass. Instead he devoted much

of his life to bringing the joy and magic of music into the lives of the

abandoned and the unwanted. He spent the better part of his career teaching

music at a foundling home, the Pietà, which was a refuge for homeless girls.

The all-girl orchestra and chorus he established there became internationally

renowned, and visitors from all over Europe came to Venice to hear them perform.

As for

his long association with Annina Girò, my many years of research did not turn

up anything to indicate they were ever anything more than good friends and

artistic collaborators. Vivaldi himself referred to their relationship as an amicizia,

which means a “close friendship.”

MJN: You make a rapid switch from Vivaldi's Venice to 1920s

Pittsburg. Social norms have certainly changed in terms of religious freedom

and gender roles, and yet many of the challenges that musicians face have

remained the same. Artists are still vulnerable to the whims of their benefactors

and unwanted attention from fans who don't respect boundaries.

SBK: As I see it, there are more similarities than

differences between the stories told in The Red Priest’s Annina and Jazz

Girl, and I was inspired to write both for much the same reasons. True,

Mary’s world—an inter-racial Pittsburgh neighborhood in the 1920s—was quite

different from the environment Annina experienced in 1720s Venice. But the

contrasts between these settings simply provide different frames for the two

heroines’ stories.

The

similarities between the stories are much more significant. Both Annina and

Mary were self-driven to master their musical gifts from an early age. Each had

serious obstacles in their way, including disinterested mothers and

dysfunctional home situations. Both girls were fortunate to attract the

attention of adult mentors who helped guide them toward achieving their goals.

Indeed,

the long, hard road to musical stardom has not changed much over the centuries.

Young women in particular have always had their own particular challenges to

face, and both Annina’s and Mary’s stories exemplify this truth. It was and

continues to be an honor and a privilege for me to share the stories of these

two unsung heroines in the history of music!