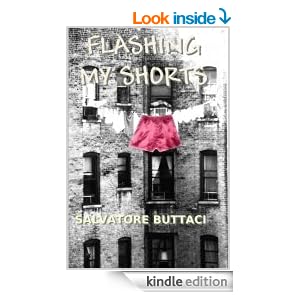

Today I would like to welcome another author from All Things That Matter Press, Salvatore Buttaci, a man of a thousand voices, who has made a name for himself writing short fiction. He is the author of two anthologies, Flashing My Shorts and 200 Shorts, as well as an Italian-American anthology A Family of Sicilians.

MJN: One of the misconceptions is that writing

flash fiction is easy, due to the length of each piece, but in reality, it's a

very demanding form, something an author "graduates" to. Each piece

has to be its autonomous universe. There are too many vignettes that are being

passed as shorts.

SB: The

brevity of flash fiction describes it, but does not define it. A short-short

fiction story must fall within a certain number of words, but the emphasis

should be placed first on the composition of words, and second, on the number.

Flash fiction is like haiku poetry: size matters, but the narrative world it

delivers must be in a sense a galaxy. Each flash is a bag of beans, yes, but a

bag of magical beans. Readers who venture into the quick read can elevate their

reading pleasure high on the beanstalk of reader satisfaction.

So what then is the responsibility of flash writers? No different

than that of short story writers, novelists, memoirists–– all those who tell a

story and therefore are required to follow the rules of storytelling. The

essential elements cannot be overlooked. An interesting, though often a simple,

plot must be developed with the right amount of narration, dialogue,

description, exposition, all the while with an eye to length. Flash authors

ride out their stories with hands tightly on the reins. They need to hook the

readers, keep them interested throughout, and then at the end let them walk

away satisfied and hungry for more flashes.

Though some call it sudden fiction, I suppose one could

say a writer does not suddenly come to writing flash. In my own case, the short

paneled stories of childhood comics, Christ’s parables, my father’s

lesson-teaching stories, the shorter fictions of reputable writers found in our

English textbooks –– all of these influenced my writing. They taught me to tell

the story but be quick about it, which encouraged me to study how-to manuals

and read short-short fiction. In doing so, I learned a story could be told in

under a 1,000 words, the key being how far I could go with edits and revisions

without hurting the story.

One of my flashes called “Fifty Cents” is found in my

book 200 Shorts. It was published in Blink/Ink in June 2010 and nominated for a

Pushcart Prize. It contains only fifty words.

Brian’s father gave him fifty cents. Brian placed church

quarter in his left trouser pocket, and his weekly allowance quarter in his

right trouser pocket.

Climbing the church steps, coin in hand, he dropped it

and watched it roll down the street grating. He patted the pocket that held his

allowance.

MJN: I already compared

you to one of my favorite actors, Lon Chaney. He was known as the "man of

a thousand faces". And you are the "man of a thousand voices".

Clearly, your repertoire spans so many styles and tones, it's hard to believe

your shorts were written by the same person. Do you feel like you are trying on

different masks, or do you think that all these voices live inside your head at

the same time?

SB: My

objective in writing 200 Shorts and Flashing My Shorts has been to allow each

protagonist to tell his or her story without the impediment of author

appearances. I am the author but I am not what or about whom I write. The

writing and arranging of different kinds of stories is a conscious effort on my

part and, yes, it likewise takes a conscious effort to restrain those voices

living inside my head from blurting out simultaneously. No writer welcomes

towers of Babel!

MJN: When you arrange your shorts in an anthology,

do you organize them according to a theme or do you deliberately create

contrast? For example, if you had one piece written in a cynical voice, would

you place it with another cynical piece for consistency or something tender and

uplifting by contrast?

SB: I

try hard to place myself in my readers’ shoes. What would they enjoy reading?

Hopefully they are my kind of reader who loves variety, so I write in more than

several genres.

I consider a book of flash fiction akin to a buffet where

diners move along this long table laden with all kinds of goodies to taste and

savor before going on to the next treat. With the offerings of flash fiction,

if a reader does not particularly like horror, the next flash might be romance

or the loss of it, adventure, mystery, crime noir, fantasy or even off-the-wall

bizarre. Sometimes flash collections do adhere to a particular theme; mine do

not. While I enjoy a good horror tale, I don’t want to read 100 or 200 of them

in the same book because it’s almost a surefire way to repeat oneself by

developing the same plot with a twist of some of its elements. I think it’s

easier and more creatively rewarding to present oneself as a writing Jack of

all genres.

MJN: You are very much

in touch with your Italian roots. Your book A Family of Sicilians, which

critics have called "one of the best books written about Sicily,

Sicilians, and Sicilian Americans." What do your family members think

about your writing career? I'm only asking because, unfortunately, most of my

family members don't understand my work.

SB: My

parents encouraged my writing as early as when I was nine. My first poem was a

gift to Mama on Mother’s Day. She read it, cried, called my father into the

room so he could read it, cry, and pat me on the back and say, “This is better

than Dante!” Of course, at nine I thought maybe Dante was an old-country friend

of my parents, some shepherd from their hill town of Acquaviva Platani, Sicily,

who scribbled poems while the sheep grazed. When I found out who Dante was (and

who I was: a kid who could never in his wildest dreams be that Master Poet), I

realized I had to keep writing for the rest of my life, not to catch up with

Dante but to please my parents.

You ask if my parents understood my work? Does one in

love truly understand what love is? Does a lack of understanding lessen love’s

intensity?

Growing up, since my first published work, a political

essay, in The Sunday New York News at fifteen, I have experienced the same

level of excitation each time I see a poem, a story, a letter, an essay, a book

of mine in publication. It is that childhood joy that never left me and I thank

my parents and my God for it daily. And may I add that I shared the good news

of each published work with my parents who would ask me to read that poem or

that story and to make a copy for the folder they lovingly kept of my writing

achievements. Now Mama and Papa are gone. After I write, my wife Sharon has

become the second person to read my work. An excellent critic, a phenomenal

reader, she has been in my writer’s corner since we married in October 1996. No

surprise that I love her more than any protagonist I’ve ever written about.

I wrote A Family of Sicilians: Stories and Poems because,

as an activist member of One Voice Coalition, an organization that objects to

and fights against discrimination against Sicilians and Sicilian Americans, I

wanted readers to see what Sicilians are really about. I included bilingual

poems (both English and Sicilian), short stories and memoirs in English about

my 1965 year in Sicily. I self-published it, managed to promote it myself in

newspapers, magazines, radio, cable TV, libraries, etc. and managing to sell a

first printing run of 1,000 copies. The book is still selling and is now

available at lulu.com.

MJN: This is a somewhat

personal question. But what the heck? That's what interviews are for. Right?

You and I have something in common: ultra conservative political and social

views. It's no secret that the world of literature and performing arts is

dominated by people with more liberal views. I often feel secluded in my

reactionary bubble. Do you feel the same? Can you form friendships with other

authors whose values are different from yours?

SB: I

am a bit leery of labeling views as liberal or conservative, ultra or

otherwise. I have found neither one exists as totally one or the other. Too

often the liberal appear conservative and the conservative, liberal. Each view

espouses ideas with which I agree and disagree. As a Christian who loves Christ

and tries to live a moral life, I object to whatever is socially- or

politically-correct and at the same time immoral, regardless of how

compassionate they seem or who advocates their acceptance, conservatives or

liberals.

As a writer I do not resort to bad language or salacious

writings. My intention as a writer is to entertain readers, not titillate them.

I believe words have a much nobler purpose than that. I suppose this is an

admission of conservative thinking. If so, let it be. I look to words that

uplift, enrich, make readers laugh and cry. Some will seek out books that will

satisfy their prurient curiosity. Some will argue such writings are realistic

because society is geared towards repeating the f-word ad nauseam or is

accustomed to indecency, but I refuse to add oil to the fire by writing to

satisfy that base level of “the way things are.”

As for other authors, I have formed friendships with many

of them and for that I am quite thankful. I have read and reviewed several of

their books. Over the years I have managed to keep certain books separate from

their authors. I may not agree with what or how they write, but in our free

society they have the right to express the ideas they choose. I may not share

their values. They may not share mine. Still, I do what I can to promote the

sale of their books, conceding that the world’s a mixed bag. Every writer is

unique in his or her slant as to what they feel will sell. I read books, I

admire books, but I do not agree with all the books I read. Those I will not

read are few: the ones that attempt to blaspheme against God, and those that

disparage religions, races, and ethnicities.

A writer of flash fiction, I do my best to encourage

readers to order my books. I do so because I feel with all my heart they are

worth the purchase price and represent good examples of what flash fiction is

all about. And to quote a recent buyer and reader, “What I like about your

short-short fiction collections, they can be read over and over again!”