Greetings, commies! Harriette Rinaldi is a fellow author

from Fireship Press. Even though we

write on different subjects, we share a commitment to illuminating historical episodes

and figures which for whatever reason do not receive sufficient attention from

the media. Today she joins us to discuss her novel Four Faces of Truth

depicting the Cambodian crisis.

MJN: Many of the Fireship authors have led professionally

fulfilling lives that are as exciting as those of their characters.

You are a former CIA officer. Many of them have served in the military

and taught at college level, including the founder of Fireship Press, our

beloved Tom Grundner. Does your previous professional activity affect your

worldview and your style of writing?

HR: Having served in many parts of the world and learning

new languages, as well as the history and culture of those countries,

undoubtedly enhanced my worldview. Prior to joining the CIA I taught French

language and literature, and studied at the Sorbonne in Paris (where all key

leaders of the Khmer Rouge had studied a decade earlier.) My father, a private

school headmaster and scholar of ancient languages, also inspired my love for

languages. I always told my students that learning another language saves one from

having a myopic view of other cultures and makes one a true citizen of the

world. As for writing style, my years of writing reports and analyses for

senior US Government policy makers instilled in me the value of a journalistic

style using an economy of words and strict adherence to precision of language.

In writing my nonfiction book, Born at

the Battlefield of Gettysburg; an African-American Family Saga, I was able

to draw upon this experience. Writing Four

Faces of Truth, however, was more liberating. Writing historical fiction

allowed me to combine techniques of fiction (dialogue, dream sequences, poetry,

suspense etc) with the conciseness of fact required for nonfiction.

MJN: You spent several years in Cambodia during the Khmer Rouge

regime. Did you feel that a certain period of time had to

pass before you started writing your novel covering

that historical episode?

HR: During my three years in Cambodia I never considered

writing about my experiences there. After retiring from the CIA I spent several

years teaching leadership seminars and, later, writing my Gettysburg book. More

recently, I realized that there are too many parallels and lessons from my time

in Cambodia that apply to what is happening elsewhere in the world today. In my

book events and talks this past year, I have stressed to audiences the uncanny

parallels between the leaders, ideology, and brutal tactics of the Khmer Rouge

and the group known as ISIS.

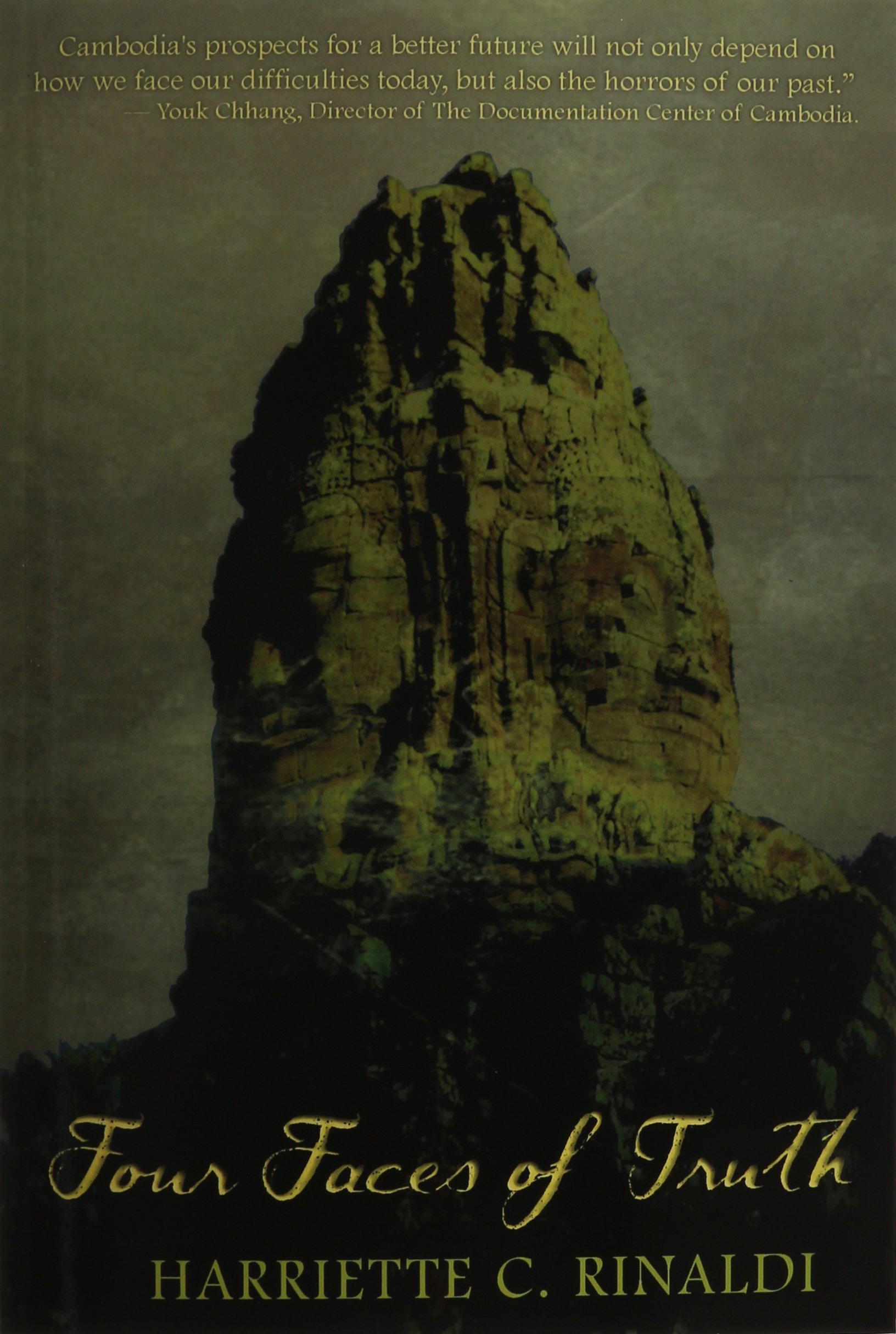

MJN: On your website you feature a photo that looks, at first glance, like a

stonehenge, but you can make out human faces. The photo is from Barry

Broman's book Cambodia: the Land and Its People.

Can you briefly tell us the story behind the monument?

HR: The photo on the cover of my book is of the great Bayon

monument at Angkor Thom built by King Jayavarman VII (1181-c.1220). In fact

there are many of these immense pineapple-shaped stone towers in the form of

human heads, with four faces—each looking out in a different geographical

direction. Although I could not visit either Angkor Wat or Angkor Thom, which

were then in the hands of the Khmer Rouge, I did meet a former guide at Angkor

who told me that these serene Buddhist-inspired countenances represent “faces

of truth” that have borne witness to all the good and all the evil which has

occurred in Cambodia over the centuries. I chose to have four narrators for my

book, each representing another perspective of what happened during the Khmer

Rouge reign of terror. Viewing events from four points of view seems in keeping

with traditional Khmer symbolism. My four fictional narrators are also “Four

Faces of Truth”, compelling readers to listen and learn from what they have

witnesses.

MJN: As a Russian born author writing about Irish history I've

encountered my share of perplexed stares. I imagine, same is true for

you, as a Caucasian author writing about Asian and African American

history. Do you find that you have to frequently advocate your choice of

subject matter?

HR: Writing instructors often tell students to write about

what they know. My Cambodia book is obviously based on my own experience and

research. My Gettysburg book is also based on a unique story I learned about as

a young child. That book was based on letters written to my great-grandfather

in 1931 (a 93 year-old Union Army veteran who fought at Gettysburg) from a man

named Victor Chambers who was born on the battlefield of Gettysburg to a

runaway slave. His beautifully written letters speak with great love and

passion for his courageous mother who walked over 200 miles from a tobacco

plantation in Virginia where she was a slave for 37 years, to her home state of

Pennsylvania so that her unborn child would be able to live in freedom. Mr.

Chambers’ letters also trace his family’s history from freedom in Dahomey (now Benin),

to slavery on a French sugar plantation in Haiti, and to ultimately to freedom

in Pennsylvania. Sadly, however, his mother was kidnapped when she was only

five years old and sold into slavery. But her grueling walk to freedom that

began when she was seven months pregnant is a testament to the resilience of

the human spirit in search of freedom (much as we see today with the thousands

of people fleeing the Middle East for a better life in Western Europe.) My

mother read Victor Chambers’ letters to her children each year on the birthday

of President Abraham Lincoln. So this story is also an important part of my own

family history.

MJN: You mention on your site that many disasters fall under the radar

of global media. Some conflicts get more coverage

than others. You mentioned that the suffering of Cambodian

people was largely ignored because there were more prominent conflicts

going on, involving the US in Vietnam. Your mission really appeals to me,

because I also believe in highlighting underexposed tragedies and unfairly

obscured figures.

HR: When I

mention the words Khmer Rouge or the name of its demonic leader, Pol Pot, the

most frequent reaction is a blank stare of non-recognition. When Pol Pot was

plotting the revolution and eventually overthrowing the Cambodian government.

America was focused on extricating itself from neighboring Vietnam and reeling

from the Watergate scandal and the impeachment of President Richard Nixon.

During Pol Pot’s reign of terror, all contact with the rest of the world was

largely inexistent—much like North Korea today. Because Cambodia was not the

victim of a major matural disaster, to which the world usually responds with

great outpouring of support and sympathy, the sufferings of its people are

still largely ignored today. Yet millions died at the hands of the Khmer Rouge,

and tens of millions remain traumatized today. I wrote this book because, as I

stated above, there are too many parallels between that regime and others in

the world today. To ignore the past is to repeat the same mistakes over and

over again.

No comments:

Post a Comment