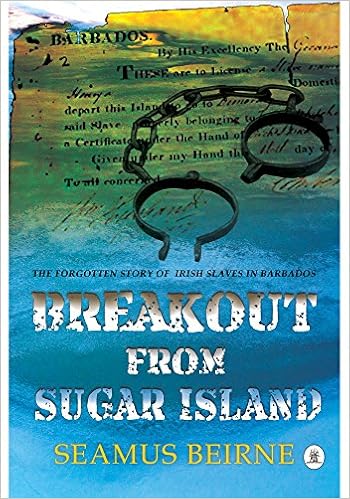

Seamus Beirne, a native of

Co. Roscommon, Ireland, opens up about the history and inspiration behind his critically

acclaimed debut novel Breakout from Sugar Island dedicated to the 60,000 Irish

slaves that perished in Barbados as casualties of Oliver Cromwell’s brutality.

He explores the Afro-Celtic bond in an Anglo-Saxon dominated society.

MJN: Given

that both the Irish and Africans were marginalized by the Protestant

Anglo-Saxon community, there was a certain sense of Afro-Celtic solidarity and

camaraderie. In the years leading up to the American Civil War, there was as

community of so-called "amalgamators" in the Five Points, interracial

families - Paddies and free blacks. Would you say that the sense of camaraderie

is still alive, especially in light of recent events involving police

brutality?

SB: I

think there is always a sense of solidarity among oppressed peoples. Despite

skin color or nationality, oppression is still oppression. We had a dramatic

example of that in the Mexican-American War when a battalion of Irish soldiers deserted

the American army and went over to Mexico. They were known as St. Patrick's Battalion,

and were nicknamed affectionately the Red Beards. Is that feeling of solidarity

vis-a-vis Irish, Mexican and African Americans alive today? It's questionable

given the antagonism of some high profile Irish Americans like Bill O'Reilly

and Sean Hannity to minorities and immigrants. Granted they do not speak for, or

represent, all Irish Americans, but an awful lot of Irish names pop up espousing

political beliefs and values, suggesting that their bearers are unaware of a

time in the 19th century when "No Irish Need Apply" signs were common

in New York and Boston.

MJN: One of the reviewers compared your style to that of Alexandre Dumas and John Millington Synge. That's a very interesting comparison, given that Dumas was known for his flighty, flippant style, while Synge was venomous and bitter. How does one reconcile the two styles? I imagine, you are likened to Dumas for the adventurous/swashbuckling element, and to Synge for your social commentary.

SB: I'm

hoping that Peter Duffy compared me to Dumas for his swashbuckling narrative

and not his flippant style. Although in truth, the Irish can be very flip and

ironic, especially in their dialogue. All one has to do is read Roddy Doyle to

get a taste of the latter. The comparison with Synge, while flattering, may

come down to this: Synge wrote, for the most part, about simple country people,

the harshness of their lives, their colorful language, and their enthrallment

to Catholicism, certain elements of which echoed their Celtic pagan past. My

story too touches on the harsh life of the average rural person of 18th century

Ireland, although my focus is not on religion per se, except in the case of the

secret agrarian society of Whiteboys. Here religion played a significant role,

with the common man being in favor of such societies and the Church hierarchy opposed.

In the novel I touch on the tension between these two.

MJN: I am absolutely tickled that you come from Co. Roscommon. My husband's ancestors are from that part of Ireland, and I've set my novels there. On your website, while discussing the separation of classes in 18th century Ireland, you say that if a servant violated the code of conduct by making eye contact with the gentry, the consequences could include flogging or worse. What would "or worse" mean in that case?

SB: It

all depended on the power broker involved. If he despised the help or his

tenants, which many of them did, then a sadistic or insecure streak might lead

to harsh punishment. Remember we are talking about a time when a poor person

could be hanged for stealing a loaf of bread. In most situations, however,

uninvited eye contact might bring no more than a rebuke. In my novel I establish

a strong bond of friendship between the landlord and an old servant. So some of

the gentry were decent people. Wasn't all black and white. In other

circumstances the punishment could be more severe. As crazy as it sounds, unsolicited

eye contact with the gentry in most European societies could be interpreted as

disrespectful or challenging.

MJN: Are there any figures in Irish history that are particularly demonized to this day? We all know that you don't mention the name of Oliver Cromwell out loud. Are there any unutterable names? Lord Lucan, perhaps?

MJN: Are there any figures in Irish history that are particularly demonized to this day? We all know that you don't mention the name of Oliver Cromwell out loud. Are there any unutterable names? Lord Lucan, perhaps?

SB: There

is one name and one name only. Cromwell.

He is the Hitler of Ireland. I don't think Lord Lucan was in the same league.

MJN: Another element of your biography that tickled me was that you had studied for priesthood. Apparently, for a young man of Irish extraction it was a very commendable path. Did your Irish Catholic upbringing had influenced your original interest in priesthood, or was it a higher calling that transcended your ethnicity?

MJN: Another element of your biography that tickled me was that you had studied for priesthood. Apparently, for a young man of Irish extraction it was a very commendable path. Did your Irish Catholic upbringing had influenced your original interest in priesthood, or was it a higher calling that transcended your ethnicity?

SB: For

centuries in Ireland Catholicism was like water to fish. During the long sway

of English occupation, it was a bulwark against the foreign foe. In those

circumstances it was hard to separate genuine love of religion from genuine

hatred of the English. After the treaty of 1921, the State and the Catholic

hierarchy became bedfellows. With the result that for ninety years Ireland was

in effect a theocracy. In those circumstances separating what was a higher

calling from what was in the cultural DNA is a difficult question to answer.

So, on a surface level what might appear as a higher calling may well have been

in the murky regions of the subconscious a far more mundane decision to deal

with the lack of prospects for self-realization in the Spartan conditions of

1950's Ireland.

MJN: Congratulations on your numerous literary awards. Can you tell me more how you obtained them? I assume you got them prior to the publication of your novel?

MJN: Congratulations on your numerous literary awards. Can you tell me more how you obtained them? I assume you got them prior to the publication of your novel?

SB: Yes

I got them prior to the novel's publication. I submitted three chapters for a reading

critique to a committee. Some of the awards were for Breakout, and some for an as-yet-unpublished novel about Ireland

during WWII.

There were English political prisoners on Barbados too and their descendants still live a peasant life on the island. Sounds like an fascinating literary novel--the sugar factories of the WI claimed many thousands of enslaved lives--one thing humans are good at is spilling one another's blood.

ReplyDeleteIndeed there were, and Scots too, but the majority were Africans and Irish. The Irish were called "Red Legs," because of their tendency to burn under the tropical sun, but the English and Scots could equally lay claim to that moniker because of their fair skin.

Delete