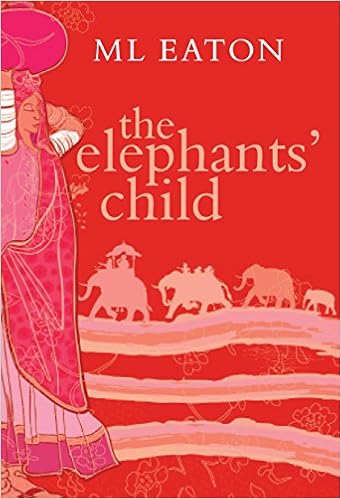

On occasion I get permission from my fellow bloggers to repost one of their reviews. Today is one of those days. Say hello to M.L. Eaton, writer of mystery thrillers with a supernatural twist. Her novel The Elephants' Child was reviewed in Before the Second Sleep blog.

______________________

One of the first things I noticed about M.L. Eaton’s The Elephants’

Child when I initially received it, was its modest volume. This didn’t take

away from what I expected it might be, but the contrast between its size and

the story power packed inside becomes a delightful discovery.

Set in post-Partition India, The Elephants’ Child is mostly

six-year-old Melanie’s story, though told in omniscient third person with brief

forays into others’ perceptions. This works well because readers are able to

get a grip on what is happening in the “adult world” while remaining anchored

in Melanie’s. At times Eaton chooses to blend the two beautifully, capturing a

resulting understanding of where the young girl acquires some of her own

thought patterns, but with her own will intact.

“Now Lakshmi was there,

insisting on holding her hands to make sure she was safe: which was mostly nice

but often a bit of a nuisance because Melanie wanted to run and play hide and

seek in the gardens and not walk properly like a little lady.”

Melanie and her family shift from Karachi to Bombay (present-day Mumbai)

when her father assumes a new position in a civil engineering project. The

little girl has had to say goodbye more times than she cares to remember,

including initially from her native England, and has a difficult time

adjusting. Moreover, she tries to reconcile grown-up behavior—“Adults were such

peculiar things: they pretended nearly all the time”—with their words,

an endeavor she finds utterly confounding. A poised and intelligent girl,

however, she draws her own conclusions, including when to trust they were

indeed telling the truth, evoking her very early childhood when her father

introduced her to the peculiar elephants and promised they were real.

With a natural affinity for animals, Melanie develops particular fondness

for the huge, grey creatures at the Hanging Gardens, where her new ayah

takes her. Over some time her patience and the elephant mother’s trust develop

and the bond between creatures and human solidifies. Melanie experiences an

awakening, with an attending greater happiness, as well as a unity in spirit

with the elephants.

This coincides with the illness and scheduled surgery of Elizabeth,

Melanie’s mother, and the young girl’s fears for her mother play out in dreams

of elephants and their deaths. She herself experiences a setback and her ayah,

Lakshmi, immerses her more deeply into the culture by teaching her about the

elephant-headed god, Ganesha, who removes obstacles, including those within.

She instructs her in the mantra, Om Gum Ganapatayei Namaha, an appeal to

the god, though later worries what the memsahib will think of this.

Through the book Eaton weaves a theme of unity, her skill often apparent

given the seeming opposites she is joining together: humans and animals,

sadness and joy, a child in an adult world, the meeting of mono- and

polytheistic cultures. It is even more telling of her talent that she

accomplishes the feat without any person or creature having to compromise who

they are.

Another technique that stands out to great effect is Eaton’s ability to

utilize descriptive language in a way that awakens readers’ senses as she lays

out any given scene. Perhaps the best example is one that introduces Melanie

herself to her new home via the Gateway to India:

“Ahead of them stretched

a magnificent panorama. The sapphire sea filled the wide deep bay of the

natural harbour, framed by the lush green of the mountains on the mainland. The

harbour itself was studded with islands, like precious stones of emerald and

jasper in a sea of liquid lapis lazuli, a shimmering deep blue flecked with

gold and dotted with white diamonds—the sails of innumerable small craft

skipping across the sea’s sparkling surface.”

In just over 100 pages, Eaton composes a small treasure of words, woven into

a portrait taking us back to a time when, indeed, all was not perfectly wed,

but where the willing could find some unity in their surroundings and take with

them remembered pieces of a land that, because it in part grew them, becomes

part of their soul. This is the case for Melanie, despite her struggles as laid

out so poignantly by the author.

It is also the sort of book that beckons for a re-read and, I suspect, will

reveal an additional something every time. Each discovery of the memoir

contained within will glisten in readers’ own memories as they reach for the

stories, not unlike digging into Mary Poppins’s small but deeply-packed bag of

rich treasures brought out to enchant and unify purpose, being and wonder.

Presented with simplicity, but certainly not simple, no matter readers’ ages,

genre preferences or unfamiliarity with the content, it is a precious and

timeless keepsake for any bookshelf.

No comments:

Post a Comment