Salutations to all of you, Connecticut Commies!

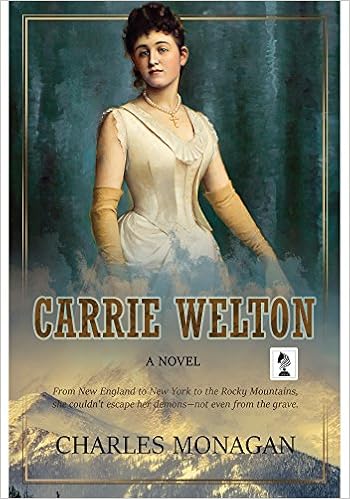

In a mood for some nutmeg? Today's guest of honor is a fellow Connecticut Commie and Penmore Press author Charles Monagan. His novel Carrie Welton is set in Waterbury, CT.

Synopsis:

Eighteen-year-old Carrie Welton is restless, unhappy, and ill-suited to

the conventions of nineteenth-century New England. Using her charm and a

cunning scheme, she escapes the shadow of a cruel father and wanders

into a thrilling series of high-wire adventures. Her travels take her

all over the country, putting her in the path of Bohemian painters,

poets, singers, social crusaders, opium eaters, violent gang members,

and a group of female mountain climbers.

But Carrie’s demons return to haunt her, bringing her to the edge of

sanity and leading to a fateful expedition onto Longs Peak in Colorado.

That’s not the end, though. Carrie, being Carrie, sends an astonishing

letter back from the grave and thus engineers her final escape—forever

into your heart.

My thoughts:

What sets Carrie Welton apart is the rarely used first person

omniscient narrative. Rarely do you see a novel in which the title

character not being the speaker. The same narrative model was used in

Jack London's The Sea-Wolf and Nabokov's Lolita. The

heroine of Charles Monagan's novel, Caroline Welton, becomes the object

of fascination to Frederick Kingsbury, a dutiful family man with an

equally dutiful and sympathetic wife. The Kingsburys become personally

invested in the emotional and social well-being of the troubled girl

next door, championing her independence and artistic growth.

Tolstoy

claims that "Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is

unhappy in its own way." While there are many variables that contribute

to each family's dysfunction, and there are many creative ways people

can sabotage their home lives, but, leaning on my personal experience,

dysfunctional families have certain "key ingredients" in common. I've

seen enough dysfunctional New England families. I've seen enough

tyrannical fathers who make occasional cameo appearances just to stomp

their feet a few times and bark. I've seen enough oblivious wives who

seek validation by throwing lavish parties. And I've seen enough lonely

children who bond with animals and neighbors than they do with their own

parents.

Monagan paints a vivid picture of social anxiety and

PTSD before those conditions were explored and labeled. His speaker,

Kingsbury, maintains an outlook that is consistent with his era. There

are references to the key Civil War battles, the draft riots in New York

City, the Bohemian art scene. It's such a daunting task to keep the

21st century author and the 19the century speaker separate. There are so

many opportunities for slip-ups and inadvertent anachronisms, and

Monagan manages to avoid them all. The most impressive feat, however, is

the exquisite, unobtrusive transition from first person limited to

first person omniscient. At some point the reader realizes that

Kingsbury describes events that did not happen before his very eyes. In

the first half of the novel, he is in close physical proximity to his

protegee. He pays painstaking attention to her body language, her

smile, her features. After Carrie moves away, he continues to chronicle

her adventures from afar, imagining what her daily life might have been.

He feels her from a distance. At the same time, Kingsbury's fascination

is refreshingly chaste. He does not devolve into a dirty old man who

becomes obsessed with the vulnerable girl next door. I admit to having

feared that the story line would head in the Lolita direction, but thankfully, it did not.

Apart from being a top-notch authentic historical novel, Carrie Welton is a commendable exercise in unorthodox narrative.

No comments:

Post a Comment