Imagine spending 34 years researching a historical figure in order to come up with an authentic fiction series. Please join me to welcome a daring, dedicated and candid author Katherine Ashe as she discusses more than three decades of research behind her Simon de Montfort series.

MJN: There is a romance writer

whose name is very similar to yours - Katharine Ashe. Do you get confused

often? I imagine many readers go on Amazon to look for your work and come up

with dozens of novels featuring damsels with bare backs and flowing locks.

KA: Katharine Ashe the romance writer came out with her first book

about five months after the first volume of Montfort was published. I

was very concerned that we would be confused but my friends in publishing

advised me that nothing could be done about it. Although she and I spell

Katherine differently (she has an a in the middle, I have an e)

Google has completely confounded us. Since she has a large publisher that makes

a point of promoting their romance writers, and since she writes several books

per year, a search turns up her works rather than mine. I've asked Amazon to do

something about this -- ideally have searches spelling-specific, but with no

luck. The up side of it is I do pick up a few readers who think they're buying

a romance, then like what they read and give me a nice customer review.

MJN: In your bio it states that

the research for your De Montfort series took almost three and a half

decades. What sources were available to you at the inception of the

project? I imagine, record-keeping has changed quite a bit.

KA: I was living in New York

City and began my researches at the New York Society Library, a private library

that was chartered by King George III and that has open stacks for members. The

NYSL is particularly rich in its history collection. After reading all the

biographies of Simon de Montfort I could get my hands on I was convinced that

scholarship on the subject was in considerable confusion.

Simon, the Earl of Leicester who founded Parliament, was often confounded with his father who led the Albigensian Crusade. And most of the British biographies, what there were of them, portrayed Simon as an ambitious tyrant -- which seemed hardly consistent with a leader who captured the country but didn't kill the king and make himself king. Fortunately the NYSL had the seven volume J. A. Giles translation of the Chronica Majora of Matthew Paris, a detailed day by day chronicle of the happenings during the years of Simon's ascendency. The New York Public Library (the Astor, Lenox Tilden Library -- that one with the lions out front) had the 19th century printings of the Chancery records of the period: Expenses of the Crown, Charters. royal letters, not consistently surviving day by day in King Henry IIl's early years but becoming daily and reliable by the later 1240s. But in many cases the Library's rare volumes were reduced to something that looked like a hamburger -- nibbled by rats into circular shape -- utterly useless. (The Chancery records now are, for the most part, available on line -- of course there was no such thing in 1977.)

By the time I was into my second year of research I realized I needed to see the real thing -- the original documents housed in the London Public Record Office, the British Library and the Bibliotheque Nationale which contains a Montfort archive including original trial notes, an autobiography by Simon prepared for his trial that coves, in brief, his experience in England and King Henry III's abuse of him. His will is also in that archive. It was a stunning experience having in my own hands these documents he handled. At that time, 1978, all the Bibliotheque required was that you not bring an open ink bottle into the room. Now it's surely much more difficult -- if not impossible -- to get access to the actual documents.

Simon, the Earl of Leicester who founded Parliament, was often confounded with his father who led the Albigensian Crusade. And most of the British biographies, what there were of them, portrayed Simon as an ambitious tyrant -- which seemed hardly consistent with a leader who captured the country but didn't kill the king and make himself king. Fortunately the NYSL had the seven volume J. A. Giles translation of the Chronica Majora of Matthew Paris, a detailed day by day chronicle of the happenings during the years of Simon's ascendency. The New York Public Library (the Astor, Lenox Tilden Library -- that one with the lions out front) had the 19th century printings of the Chancery records of the period: Expenses of the Crown, Charters. royal letters, not consistently surviving day by day in King Henry IIl's early years but becoming daily and reliable by the later 1240s. But in many cases the Library's rare volumes were reduced to something that looked like a hamburger -- nibbled by rats into circular shape -- utterly useless. (The Chancery records now are, for the most part, available on line -- of course there was no such thing in 1977.)

By the time I was into my second year of research I realized I needed to see the real thing -- the original documents housed in the London Public Record Office, the British Library and the Bibliotheque Nationale which contains a Montfort archive including original trial notes, an autobiography by Simon prepared for his trial that coves, in brief, his experience in England and King Henry III's abuse of him. His will is also in that archive. It was a stunning experience having in my own hands these documents he handled. At that time, 1978, all the Bibliotheque required was that you not bring an open ink bottle into the room. Now it's surely much more difficult -- if not impossible -- to get access to the actual documents.

What was

available at the British Library went far beyond basic records. The library was

in the process of converting call numbers and out in the hall there was a long

row of oak card catalogues where the old numbers were coordinated with the new.

I'd brought with me the old numbers from 19th and early 20th century

biographies but when I sent the documents' new numbers in sometimes I got the

right thing, sometimes not. (Had I miscopied the numbers? Perhaps my good luck.)

So I experimented by varying the numbers and got quantities of materials, some

of which may have languished unread for centuries -- not necessarily things

directly pertaining to Simon, but of the period.

There were boxes of seals (including Simon's wife's actual seal.) There were snippets. But mostly there were scrolls -- delivered with a pair of velvet covered bricks. The idea was to place a brick at the left hand edge of the scroll, unroll a bit and set a brick at the right hand to hold the scroll open, then move the bricks along as your read so the scroll rolled up behind the left brick, and unrolled under the right brick. These 13th century documents were written in a highly legible style called Chancery script which was clear and generally about 13 pts. in size. Virtually every literate person learned to write in this very clear style that can almost be compared to typewriting. The letters were formed much like the font I've used for the title Montfort on my book covers. The documents were in the French of the period or in Latin of course, but spelling was utterly free, even inventive. Simon's will is written by his son Henry's hand; Henry spells his own name five different ways.

Also of major importance to me was seeing first hand the places that were significant in Simon's life. I traveled through France with a friend, Clara Pierre. She was writing a book on a 12th century troubadour and her sites and mine were somewhat interwoven. Some of the places I went to in France and in Britain were so changed in 700 years that nothing much could be ascertained but the slope of the ground -- and even that might have changed. Others were redolent with spirit -- especially Lincoln Cathedral.

Returning home, I amassed every book I could find on the life of the period; the beginnings of theater in the guilds' tableau (mentioned by MatthewParis), travel on horseback, food, agriculture and husbandry, banking and finance, religious beliefs and practices -- every aspect of life. There were extant letters from Simon's friends, Franciscan Bishop Grosseteste and Adam March, that had accompanied books lent to Simon. So of course I read those books. I found similarities of his battle plan at Lewes to Arthur's battle at Autun. The temporary change of his lion emblem to a lily when he was in Gascony linked to his current reading of St. Jerome's Commentaries on the Book of Jobe. Details came to life. Pieces fit together with links of purpose. I was able to obtain two complete copies of Mathew Paris's Chronicle published in the early 1600s and checked them against the Giles translation.

There were boxes of seals (including Simon's wife's actual seal.) There were snippets. But mostly there were scrolls -- delivered with a pair of velvet covered bricks. The idea was to place a brick at the left hand edge of the scroll, unroll a bit and set a brick at the right hand to hold the scroll open, then move the bricks along as your read so the scroll rolled up behind the left brick, and unrolled under the right brick. These 13th century documents were written in a highly legible style called Chancery script which was clear and generally about 13 pts. in size. Virtually every literate person learned to write in this very clear style that can almost be compared to typewriting. The letters were formed much like the font I've used for the title Montfort on my book covers. The documents were in the French of the period or in Latin of course, but spelling was utterly free, even inventive. Simon's will is written by his son Henry's hand; Henry spells his own name five different ways.

Also of major importance to me was seeing first hand the places that were significant in Simon's life. I traveled through France with a friend, Clara Pierre. She was writing a book on a 12th century troubadour and her sites and mine were somewhat interwoven. Some of the places I went to in France and in Britain were so changed in 700 years that nothing much could be ascertained but the slope of the ground -- and even that might have changed. Others were redolent with spirit -- especially Lincoln Cathedral.

Returning home, I amassed every book I could find on the life of the period; the beginnings of theater in the guilds' tableau (mentioned by MatthewParis), travel on horseback, food, agriculture and husbandry, banking and finance, religious beliefs and practices -- every aspect of life. There were extant letters from Simon's friends, Franciscan Bishop Grosseteste and Adam March, that had accompanied books lent to Simon. So of course I read those books. I found similarities of his battle plan at Lewes to Arthur's battle at Autun. The temporary change of his lion emblem to a lily when he was in Gascony linked to his current reading of St. Jerome's Commentaries on the Book of Jobe. Details came to life. Pieces fit together with links of purpose. I was able to obtain two complete copies of Mathew Paris's Chronicle published in the early 1600s and checked them against the Giles translation.

Over the years,

as I kept searching, more and more original material turned up -- especially

regarding religious practices such as the Churching of the Queen and the

millennial and messianic beliefs that the Church was attempting to suppress --

beliefs that coalesced around Simon and his movement to give the common man a

voice in government.

And I kept asking the questions: What is the significance of this event? What seemed to be its repercussions? What's the point of view of the person who wrote this piece of evidence? Simon had literally devout followers and ferocious enemies and everything that was written touching him in his own time -- and ever after -- has been colored by these prejudices. Where could the truth lie? Or at least, how would Simon perceive the truth?

MJN: In one of our conversations you mentioned that your goal was to portray Simon de Montfort in a more realistic light, without the heroic aura shrouding him in other works of fiction. As a historical writer myself, I cannot figure out what it is the readers want, fantasy or gritty reality. There are those who want an obscure figure glamorized and mythologized. And then there are those who want to see a more sober portrayal of someone who currently resides on the Olympus.

KA: I have no idea what readers want in historical novels, and I suspect the major book publishers have no idea either or we wouldn't have so many headless women book covers. I've pursued my own interest and, happily, there are readers willing to go along on my quest with me. Montfort the Early Years was on the Amazon historical fiction best seller list for 30 weeks (March to October 2013) so I guess that says something about readers' willfulness.

As for approach, I personally don't respond well to romanticizing. My goal has been to try to understand Simon realistically and in terms of his own time. I believe that to portray a person of the past according to the tastes and prejudices of the 20th or 21st century is to do a severe disservice to that person and to misguide the history student. The challenge for me as a writer was first to understand the values, beliefs and mind-set of the 13th century, then to convey them as if they were a part of my reader's normal world.

Much of historical fiction is written as entertainment -- I have no problem with that. I've had a problem with some readers of popular historical fiction who mistake it for accurate history and criticize me because I don't say the same things their favorite author says. But it would have been a sorry waste of time if my thirty-five years of research hadn't turned up some new information and insights.

Yes, I do say things that other novelists, and even historians, don't say. For this reason I've added an extensive Historical Context section (about 10% of each volume of Montfort) giving my sources and the reasons for my interpretations. And I've made it clear in the preface of each book that I've chosen to write my work on Simon de Montfort as a novel rather than a scholarly biography because there's so much -- especially regarding Simon's and King Henry's motivations -- that I wanted to explore with the freedom of informed speculation that novel writing presumably offers. But I've never bent the history for the sake of literary form and only Volume II. Montfort The Viceroy has emerged, accidentally, as a properly shaped novel.

It happens that Simon's life was so loaded with real tensions and drama that all four book are good reading anyway. Where else can you find anyone who in a mere ten years goes from penniless petitioner to the King's best friend, to the King's brother-in-law --married to a nun, to suspected father of the heir to the throne, to outcast exile, to elected Viceroy of Jerusalem, to leader of a war against his King -- to King's best friend? And that's only the beginning of Simon's chaotic life.

And I kept asking the questions: What is the significance of this event? What seemed to be its repercussions? What's the point of view of the person who wrote this piece of evidence? Simon had literally devout followers and ferocious enemies and everything that was written touching him in his own time -- and ever after -- has been colored by these prejudices. Where could the truth lie? Or at least, how would Simon perceive the truth?

MJN: In one of our conversations you mentioned that your goal was to portray Simon de Montfort in a more realistic light, without the heroic aura shrouding him in other works of fiction. As a historical writer myself, I cannot figure out what it is the readers want, fantasy or gritty reality. There are those who want an obscure figure glamorized and mythologized. And then there are those who want to see a more sober portrayal of someone who currently resides on the Olympus.

KA: I have no idea what readers want in historical novels, and I suspect the major book publishers have no idea either or we wouldn't have so many headless women book covers. I've pursued my own interest and, happily, there are readers willing to go along on my quest with me. Montfort the Early Years was on the Amazon historical fiction best seller list for 30 weeks (March to October 2013) so I guess that says something about readers' willfulness.

As for approach, I personally don't respond well to romanticizing. My goal has been to try to understand Simon realistically and in terms of his own time. I believe that to portray a person of the past according to the tastes and prejudices of the 20th or 21st century is to do a severe disservice to that person and to misguide the history student. The challenge for me as a writer was first to understand the values, beliefs and mind-set of the 13th century, then to convey them as if they were a part of my reader's normal world.

Much of historical fiction is written as entertainment -- I have no problem with that. I've had a problem with some readers of popular historical fiction who mistake it for accurate history and criticize me because I don't say the same things their favorite author says. But it would have been a sorry waste of time if my thirty-five years of research hadn't turned up some new information and insights.

Yes, I do say things that other novelists, and even historians, don't say. For this reason I've added an extensive Historical Context section (about 10% of each volume of Montfort) giving my sources and the reasons for my interpretations. And I've made it clear in the preface of each book that I've chosen to write my work on Simon de Montfort as a novel rather than a scholarly biography because there's so much -- especially regarding Simon's and King Henry's motivations -- that I wanted to explore with the freedom of informed speculation that novel writing presumably offers. But I've never bent the history for the sake of literary form and only Volume II. Montfort The Viceroy has emerged, accidentally, as a properly shaped novel.

It happens that Simon's life was so loaded with real tensions and drama that all four book are good reading anyway. Where else can you find anyone who in a mere ten years goes from penniless petitioner to the King's best friend, to the King's brother-in-law --married to a nun, to suspected father of the heir to the throne, to outcast exile, to elected Viceroy of Jerusalem, to leader of a war against his King -- to King's best friend? And that's only the beginning of Simon's chaotic life.

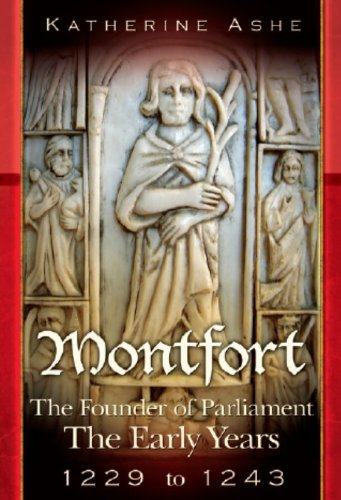

MJN: The background image on

the cover on all books is the same, with the different stain color. Can

you tell us more about the image and what it symbolizes?

KA: The image I've used for the cover of all four volumes of

Montfort is a 13th century ivory that may originally have been mounted on a

book cover, or may have served as a votive object on its own. (It was

re-framed, probably in the 19th century.) The central figure appears to be

Christ of Palm Sunday, but the surrounding saints, and the saints on the facing

panel (which I've reproduced for the back cover of Vol IV, Montfort the

Angel with the Sword) give the ivory perhaps another meaning. Most of

these saints either have connetions to England, or to the curbing of temporal

power, or have personal connections to Simon. For a full discussion of the

iconography of the ivory see my web site: http://simon-de-montfort.com/about/about-the-ivory-of-the-saints/

What has this votive object to do with Simon de Montfort? Here's a little of the background of beliefs in Simon's time:

In the 12th century a theologian named Joachim de Flore posited that there were three phases to the history of man. The Age of the Father, characterized by tribal life. The Age of the Son, with the rise of the Church and nations. And the Age of the Holy Ghost in which, over a period of a thousand years, the Church and nations would disintegrate into a single World Order governed by the free vote of the common man inspired directly by the Holy Spirit. The thousand years of this New Age, according to Joachim, would begin in the year 1260.

At first Joachim's teachings were embraced by the Church but, as the mid 13-th century approached, popes realized what a threat this theology posed to the existing power structure. Joachim's works were banned and burned, and the Church embraced the static, immutable and hierarchical theology of Thomas Aquinas. But Joachim's theology continued to be taught, clandestinely, by the Franciscans and Dominicans. (Notably by Simon's Franciscan friends Grosseteste and Marsh, successive Provosts of Oxford.)

When in the year 1258 the lords of England rebelled against King Henry III and framed a constitution for an elective government that had power over the King (the Provisions of Oxford), many of the clerics who participated were Joachite in their beliefs. And when (due to the poisoning of most of the rebel lords by the King's half-brothers) Simon de Montfort, singlehandedly and very capably, put the Provisions into effect, creating the first elected Parliament, the clerics took him to be the Messiah of the New Age.

Many people literally believed that Simon de Montfort was the Angel of the Apocalypse, or even the Risen Christ. After his death and dismemberment at the battle of Evesham, a spring came forth as his body was lifted from the ground. The spring was found to have magical curative powers, and the belief in Simon de Montfort as the Risen Christ became a rapidly spreading new religion with a strong political base of liberty and equality. (Rishanger's Chronicle is a list of miracles accomplished by the deceased Simon.)

The religion of course was outlawed. Taking water from the spring became a capital crime. Even the mention of Simon's name in any but the most disparaging way became an act of treason. And the memory of Simon de Montfort was suppressed -- except of course one might speak ill of him as most British writers have continued to do to this day.

Could the ivory be a survivor of that clandestine religion? And might the Christ figure be a nearly contemporary depiction of Simon de Montfort? I've used it for my book covers on the chance that it is.

While memory of Simon was suppressed, Joachim's theology never was completely quenched. His Three Ages have reappeared in the French Revolution (the Jacobins literally were followers -- even to holding their meetings in the refectory where Joachim taught), the Third Reich and the most fundamental beliefs of Marxism -- but also in the founding of our own democracy: "We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal..." That is the essence of Joachim's Third Age.

MJN: I don't mind asking you this question, because I am not afraid of how I'm perceived at the Historical Novel Society. I'm not afraid of burning any bridges, since any bridges I attempted to build were torn down at the very foundation (insert a sardonic grin). Do you believe that those societies are useful for networking and marketing purposes, or do you find them highly political and corrupt? I could write an entire novel about the politics of the HNS on Facebook.

KA: I don't actually have much to say about the Historical Novel Society. I'm not presently a member and I've never been very involved. In June of 2010, when my first volume, Montfort the Early Years, had been out for about four months, I did a web search of my own name. At the top of the search I found there had been a discussion of me and of my book going on for some weeks on a chat thread belonging to HNS. It began with Susan Higginbotham asking Sharon Penman (who had included Simon as a major character in a novel she'd written some years past) what she thought of someone who said Simon had an affair with the Queen. Penman responded that it was early in the morning and she wasn't current on her research but that anyone who said that was committing a sin.

This is an object lesson in the care one ought to take in what one says early in the morning. Higginbotham continued the discussion over weeks, gathering other authors to denounce me. It was claimed essentially that I wrote pornography -- although at that point the discussion seemed to be of my portrayal of Eleanor of Aquitaine whom I've never written about. None of the well known authors who were busy defaming me had read my book. When they found a fellow who actually had a copy of Montfort they coached him in how to write a slamming review. Realizing of course that their accusations were totally unrelated to what I'd written, he dropped out of the discussion, contacted me and we became friends.

I entered a complaint with Richard Lee and he took most of the discussion thread off the internet. But the attackers had roused their friends and fans. The attacks moved to my Facebook page with belligerent questions that I answered politely and very specifically, receiving in return co-ordinated responses that I refused to answer questions. The matter became so ugly that my FB friends urged me to ban these people and I did.

By then the target was Goodreads where I went from consistent praise for my books to attacks including the use of the word whore, and death threats. I was attacked at Independent Authors Guild, where my query as to Amazon's and Goodreads' legal responsibility regarding threats and harrassment was reversed to make me seem to be the person doing the threatening. Then the threats and abuses I supposedly had committed were retailed through the internet.

The viciousness of attack reached a new high when a systems savvy blogger wrote for my Amzon pages a customer review that was riddled with shallow and bogus "scholarship" in an attempt to prove that my books were worthless. Then the blogger, using the "campaign votes" ("did this review add..."), had her blog-readers vote up her review and vote down my 24 5-star reviews so that only her review could be seen. When a reader of my books attempted to counter this review, his blogs were attacked. When he traced attacks to a computer in a school in San Diego and informed the school authorities how their computer was being used, he was accused of physically stalking and terrorizing a woman.

The very worst for me came shortly after the deft customer review attack, when spyware was introduced into my computer and all my internet links were seized, their passwords changed and idiotic messages posted as if they had come from me. I thought something had gone haywire with my computer. But when, after about two weeks of this, I attempted to reset my Facebook password for the fifth time, I got a message that my computer had already done so seven hours earlier. That was utterly impossible. Facebook advised me to call the police. I did, and they sent me to the FBI. An agent there coached me on how to cope with the spyware.

The attacks were becoming ever more heated on my Amazon page and at Goodreads when I was discovered by a group called :Stop the Goodreads Bullies”. A war then developed in the "campaign votes" for the all-engulfing 1-star review. I'd never gotten more than three or four such votes prior to the attack; now I was approaching a hundred votes.

What has this votive object to do with Simon de Montfort? Here's a little of the background of beliefs in Simon's time:

In the 12th century a theologian named Joachim de Flore posited that there were three phases to the history of man. The Age of the Father, characterized by tribal life. The Age of the Son, with the rise of the Church and nations. And the Age of the Holy Ghost in which, over a period of a thousand years, the Church and nations would disintegrate into a single World Order governed by the free vote of the common man inspired directly by the Holy Spirit. The thousand years of this New Age, according to Joachim, would begin in the year 1260.

At first Joachim's teachings were embraced by the Church but, as the mid 13-th century approached, popes realized what a threat this theology posed to the existing power structure. Joachim's works were banned and burned, and the Church embraced the static, immutable and hierarchical theology of Thomas Aquinas. But Joachim's theology continued to be taught, clandestinely, by the Franciscans and Dominicans. (Notably by Simon's Franciscan friends Grosseteste and Marsh, successive Provosts of Oxford.)

When in the year 1258 the lords of England rebelled against King Henry III and framed a constitution for an elective government that had power over the King (the Provisions of Oxford), many of the clerics who participated were Joachite in their beliefs. And when (due to the poisoning of most of the rebel lords by the King's half-brothers) Simon de Montfort, singlehandedly and very capably, put the Provisions into effect, creating the first elected Parliament, the clerics took him to be the Messiah of the New Age.

Many people literally believed that Simon de Montfort was the Angel of the Apocalypse, or even the Risen Christ. After his death and dismemberment at the battle of Evesham, a spring came forth as his body was lifted from the ground. The spring was found to have magical curative powers, and the belief in Simon de Montfort as the Risen Christ became a rapidly spreading new religion with a strong political base of liberty and equality. (Rishanger's Chronicle is a list of miracles accomplished by the deceased Simon.)

The religion of course was outlawed. Taking water from the spring became a capital crime. Even the mention of Simon's name in any but the most disparaging way became an act of treason. And the memory of Simon de Montfort was suppressed -- except of course one might speak ill of him as most British writers have continued to do to this day.

Could the ivory be a survivor of that clandestine religion? And might the Christ figure be a nearly contemporary depiction of Simon de Montfort? I've used it for my book covers on the chance that it is.

While memory of Simon was suppressed, Joachim's theology never was completely quenched. His Three Ages have reappeared in the French Revolution (the Jacobins literally were followers -- even to holding their meetings in the refectory where Joachim taught), the Third Reich and the most fundamental beliefs of Marxism -- but also in the founding of our own democracy: "We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal..." That is the essence of Joachim's Third Age.

MJN: I don't mind asking you this question, because I am not afraid of how I'm perceived at the Historical Novel Society. I'm not afraid of burning any bridges, since any bridges I attempted to build were torn down at the very foundation (insert a sardonic grin). Do you believe that those societies are useful for networking and marketing purposes, or do you find them highly political and corrupt? I could write an entire novel about the politics of the HNS on Facebook.

KA: I don't actually have much to say about the Historical Novel Society. I'm not presently a member and I've never been very involved. In June of 2010, when my first volume, Montfort the Early Years, had been out for about four months, I did a web search of my own name. At the top of the search I found there had been a discussion of me and of my book going on for some weeks on a chat thread belonging to HNS. It began with Susan Higginbotham asking Sharon Penman (who had included Simon as a major character in a novel she'd written some years past) what she thought of someone who said Simon had an affair with the Queen. Penman responded that it was early in the morning and she wasn't current on her research but that anyone who said that was committing a sin.

This is an object lesson in the care one ought to take in what one says early in the morning. Higginbotham continued the discussion over weeks, gathering other authors to denounce me. It was claimed essentially that I wrote pornography -- although at that point the discussion seemed to be of my portrayal of Eleanor of Aquitaine whom I've never written about. None of the well known authors who were busy defaming me had read my book. When they found a fellow who actually had a copy of Montfort they coached him in how to write a slamming review. Realizing of course that their accusations were totally unrelated to what I'd written, he dropped out of the discussion, contacted me and we became friends.

I entered a complaint with Richard Lee and he took most of the discussion thread off the internet. But the attackers had roused their friends and fans. The attacks moved to my Facebook page with belligerent questions that I answered politely and very specifically, receiving in return co-ordinated responses that I refused to answer questions. The matter became so ugly that my FB friends urged me to ban these people and I did.

By then the target was Goodreads where I went from consistent praise for my books to attacks including the use of the word whore, and death threats. I was attacked at Independent Authors Guild, where my query as to Amazon's and Goodreads' legal responsibility regarding threats and harrassment was reversed to make me seem to be the person doing the threatening. Then the threats and abuses I supposedly had committed were retailed through the internet.

The viciousness of attack reached a new high when a systems savvy blogger wrote for my Amzon pages a customer review that was riddled with shallow and bogus "scholarship" in an attempt to prove that my books were worthless. Then the blogger, using the "campaign votes" ("did this review add..."), had her blog-readers vote up her review and vote down my 24 5-star reviews so that only her review could be seen. When a reader of my books attempted to counter this review, his blogs were attacked. When he traced attacks to a computer in a school in San Diego and informed the school authorities how their computer was being used, he was accused of physically stalking and terrorizing a woman.

The very worst for me came shortly after the deft customer review attack, when spyware was introduced into my computer and all my internet links were seized, their passwords changed and idiotic messages posted as if they had come from me. I thought something had gone haywire with my computer. But when, after about two weeks of this, I attempted to reset my Facebook password for the fifth time, I got a message that my computer had already done so seven hours earlier. That was utterly impossible. Facebook advised me to call the police. I did, and they sent me to the FBI. An agent there coached me on how to cope with the spyware.

The attacks were becoming ever more heated on my Amazon page and at Goodreads when I was discovered by a group called :Stop the Goodreads Bullies”. A war then developed in the "campaign votes" for the all-engulfing 1-star review. I'd never gotten more than three or four such votes prior to the attack; now I was approaching a hundred votes.

I'd achieved a

sort of fame as a target of author bullying. One reader of my books posted a

praising review only to have it immediately loaded with vicious and personal

attack comments. The reviewer took down the review and reposted it, thus

sheering off the comments. The comments were reposted; the review was taken down

again and reposted. Over the course of a weekend the review was taken down and

reposted 52 times. Finally the reviewer abandoned that account and reposted the

review under a new account name.

The time attackers seem willing to spend on viciousness is bizarre. During the spyware episode 150 "likes" were posted on my FB page for mindless TV situation comedies. It so happens that I don't have a working TV. The question voiced so often is: don't these people have anything better to do? It seems not.

Ultimately, with several authors the targets of this extraordinary deluge of abuse, Amazon took action and not only changed its algorithms for customer reviews but bought Goodreads and removed attacks there.

Regarding the Historical Novel Society -- the management certainly did treat me fairly. They have a problem in that some of their foremost members, authors with lengthy careers of successful novel writing, have little sense of responsibility. They apparently feel free to commit a sort of vigilantism against any author who's oblivious to seeking their favor and writes of history differently than they do. These authors are not representative of the Society as a whole, and the Society unfortunately seems unable to find a way to deal with the problem.

The time attackers seem willing to spend on viciousness is bizarre. During the spyware episode 150 "likes" were posted on my FB page for mindless TV situation comedies. It so happens that I don't have a working TV. The question voiced so often is: don't these people have anything better to do? It seems not.

Ultimately, with several authors the targets of this extraordinary deluge of abuse, Amazon took action and not only changed its algorithms for customer reviews but bought Goodreads and removed attacks there.

Regarding the Historical Novel Society -- the management certainly did treat me fairly. They have a problem in that some of their foremost members, authors with lengthy careers of successful novel writing, have little sense of responsibility. They apparently feel free to commit a sort of vigilantism against any author who's oblivious to seeking their favor and writes of history differently than they do. These authors are not representative of the Society as a whole, and the Society unfortunately seems unable to find a way to deal with the problem.

No comments:

Post a Comment