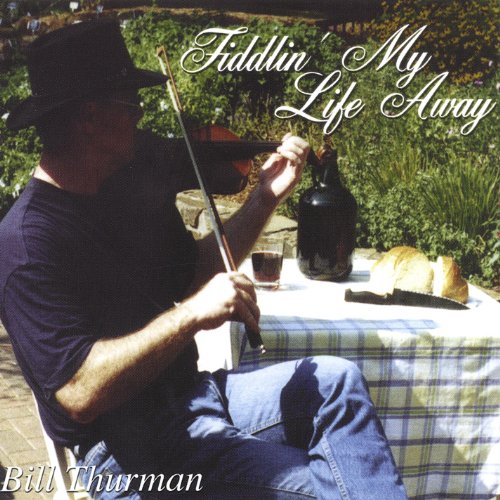

Every once in a while, in the process of researching a particular era for your next historical novel, you stumble across a literary or musical gem that introduces you to a new realm of beauty. Sometimes it's a familiar tune with a new twist. This is how I came across Bill Thurman's music. Bill is multi instrument musician. His repertoire spans broad classical and folk selection. He was kind enough to open up about his career as performer and teacher, his inspiration and collaboration with other artists. Bill is also a sarcoma survivor. He is very candid about overcoming this challenge. The title of his last album is "Nothin' but Fiddle and a Sarcoma Survivor." Please, check out his music. His CDs make a great gift for those who like early and folk music.

MJN: You were born in

Nashville and later moved to Memphis. It is a well known fact that folk and

country music are very prominent in the South. Do you feel that your renditions

of European classics have been influenced by the Southern flavor?

BT: To me, regional

differences in musical dialectics are really similar to the differences in

language dialects. I grew up with the blues, jazz, Elvis and old

"country" as well as classical music like Bach, Mozart, etc. In my

teens I continued to hear more music from around the world like Rimsky-Korsakov

and Mussorgsky as well as Jewish and Arabic music. Much of that was because I

played violin and viola in orchestras. I was also a member of the Memphis

Symphony for years. In my heart I have always been a musical internationalist,

even though I have loved all kinds of stuff called "American music."

Like one of my old teachers stated, "If it's good music, I want to play it

no matter where it comes from."

My voice and my playing and

phrasing definitely has a "southern accent" about it. It's the

culture that I grew up in. I would say that is probably true for most people,

wherever they have come from. I am pretty good though about imitating other

dialects and accents from different cultures or countries. It's my musical

"ear." In some of the songs and instrumentals I have played, I have

done several different accents within the same piece of music.

MJN: You teach fiddle and

violin. What are some of the most popular requests from your students? Are

there any skills and/or "touches" they are trying to cultivate?

BT: Most of the students

I have received simply wanted to learn to be a "fiddler" or possibly

a "violinist." The sad truth is that most of them did not have the

time or the patience or the basic "drive" to listen, learn and

WORK/play at it. Being a good or great musician takes a combination of things,

not just one or two. A lot of them wanted to sound like one of their musical

Heroes. But I often said, "you've got to make Mary Had A Little Lamb or

Twinkle Little Star sound GOOD before you can hope to sound like one of your heroes.

If they wanted to hear some

good country fiddlin' I would play them some of it. If they wanted to hear some

good jazz or blues I would play them some. But still they MUST practice and

take the time and trouble. If they don't do that, they can't get better. I also

tried to teach them all how to read musical notation as well as possible, and

to appreciate the difference between "reading" the music and

"hearing" the music. My students who had already had some training and

discipline seemed to do a good bit better when trying to learn new things.

MJN: You have performed some

of the most iconic pieces like La Rotta and The Foggy Dew, pieces that

will be recognized even by those who are not passionate fans of Renaissance or

traditional folk music. So many people don't know what they are missing. What

do you think is the most effective way to popularize some of the forgotten

masterpieces? How do you take your music and put it in front of the people who

did not know it existed?

BT: For music like La Rotta and The Foggy Dew as well as other old seldom heard music, I often will

record another new album. My latest one is called, "Nothin But Fiddle And

A Sarcoma Survivor." It has a combination of musical styles on it, and

some that are rarely heard. Like "Sugar in the Gourd", an old

Appalachian fiddle tune. Like Black and White, and old jazz violin tune from

Django Reinhardt and Stephane Grappelli. Also "Glory Be To God", a

southern Black Gospel song that I learned at an African American church long

ago. When I speak and play in public places I will often play these tunes and

songs to people who have never heard them before. Most of the people like it

when I do that.

MJN: It is no secret that

Renaissance Fairs are filled with anachronisms and people seeking escape from

daily routines, not necessarily seeking a better understanding of a particular

era. At the same time, for many people, it's the only gateway into another

century. Have you made any valuable professional / artistic connections at such

events with people who truly understood and appreciated early music?

BT: Yes, I have met

some wonderful people because of Renaissance Fairs, Celtic Music fests and

others. I love Greek music. I have gone to quite a few of the Greek food fests

just to hear the great music AND sample the delicious food. Yes, I have made

valuable connections with people from ancient music fan clubs as well as modern

music circles. I have met good people from all over the world because of my

lifetime involvement with music.

MJN: One of my favorite videos

on your site is that of you playing La Rotta and Kristy Barrington performing

the interpretive dance. La Rotta, an Italian piece, is said to be written by a

Hungarian composer. So many Medieval and Renaissance pieces are marked as

"Anonymous". Did composers strive or anonymity, or were those folk

tunes truly a product of collective creative process?

BT: I believe that most

of these ancient folk music tunes whether they come from Russia, Ireland,

Scotland, Scandinavia, Italy or England and Germany were born from one group or

one individual at a CERTAIN point and then just played and spread around to

different parts of the original areas and some even farther to other countries.

Most of these people could not read, but often had a keen ear for music - true

folk musicians in any country. Some would travel and teach their music to

others BY EAR. Almost always the music will have all these regional variations,

but a good chunk of the Old flavor will often remain. Some are better at that

than others. :)

In Spain, North Africa,

Central Africa and the Middle East, you know that much of this same idea has to

be true. Most musicians for a long time have learned by what they heard, not by

what they read on a piece of paper. However I am a firm believer in learning to

read!

The "collective

creative process" is like The Great Ocean of Life where the little streams

and creeks flow into the larger rivers and the rivers flow into the seas and

largest lakes and then the oceans of the world. Some in this process have

become truly universal. Every country has contributed. To me this is one of the

great beauties of music and art.

No comments:

Post a Comment